At InCabin Europe 2025, Siddartha Khastgir, Head of Safe Autonomy at WMG, University of Warwick and Soyeon Kim, Assistant Professor at the University of Warwick, gave a tutorial on the importance of remote operators for autonomous, Level 4 services. The session emphasised that such systems cannot function safely without human oversight, and human factors in remote operations must therefore be integrated into the design from the outset.

Why Remote Operations Matter

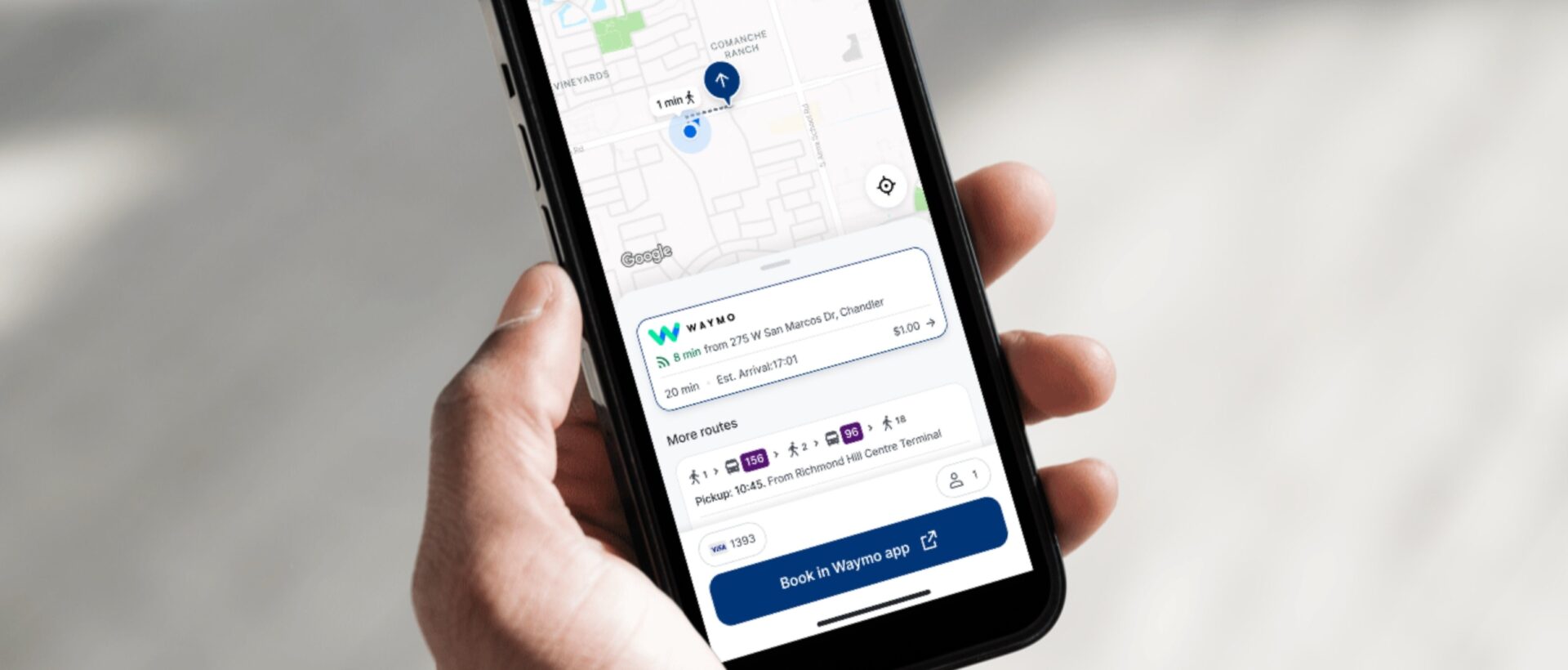

The session opened with the clear assertion that you cannot have safe autonomous driving without remote operations. Even the most advanced systems, such as Waymo’s robotaxi service, rely on human support from a distance. Although these vehicles are presented as self-driving, remote operators remain essential for maintaining safety, managing unexpected situations and addressing operational edge cases.

Remote operations refer to the control, management, or supervision of a vehicle from a distance. This includes:

Remote Monitoring – Continuous observation of vehicles’ performance and operational status, without direct control. Operators watch, detect anomalies, and provide situational oversight but do not intervene directly.

Remote Assistance – An event-driven model where the vehicle requests guidance. A human operator might confirm whether a detected object is an obstacle or provide a waypoint for the vehicle to follow. For Waymo, this role is carried out by ‘Fleet Response Specialists‘ who respond when the system encounters uncertainty, such as a blocked junction or during complex roadworks.

Remote Driving – The highest level of intervention, where a human takes control of steering, braking or acceleration. Two subtypes exist:

- Continuous Remote Driving, in which a vehicle is piloted entirely from afar (such as Germany’s Vay operating low-speed vehicles)

- Time-Bound Remote Driving, where a remote operator takes over briefly when the automated system encounters a limitation.

While the first two roles support automated operation, the third effectively replaces it, albeit temporarily. This level of human involvement introduces significant technical and regulatory challenges, particularly concerning latency, liability and safety in emergency situations. The question of accountability for a remote driver is especially complex, as human error may be influenced by factors such as video transmission delays or the absence of physical feedback from the vehicle.

Regulation and Reality

International regulators are starting to recognise the need for remote operation frameworks. A forthcoming UN regulation on automated driving systems, due to take effect in December 2025, includes clauses covering remote operation functions. However, these are technologically neutral and therefore do not specify practices.

Despite this neutrality, no Level 4 service currently operates without some form of remote oversight. Companies such as Waymo, Cruise and WeRide all depend on remote operations to support their fleets. Khastgir noted that, when active, Cruise utilised around 1.5 remote operators per vehicle, while Waymo is currently believed to maintain a one-to-one ratio between operators and cars.

The Human Factors Challenge

Arguably, the human element in these operations is frequently treated as an afterthought in the design of automated systems, which are primarily engineered to drive independently. Khastgir and Kim noted that human factors are often added retrospectively rather than integrated from the outset. As a result, human error is frequently seen as the cause of failure, when in many cases it is a symptom of inadequate system design.

At InCabin Europe, three human factors were identified as particuarly crucial to remote operations:

Situational Awareness – The ability of an operator to perceive, comprehend and predict events. Simply showing data on a screen does not mean the operator truly understands it — an issue illustrated by subtle visual cues in some driver-assist interfaces, such as Tesla’s barely noticeable indicator light for Autopilot engagement.

Workload – Both mental and physical demands affect performance. Too much workload leads to stress and mistakes, but too little induces boredom and lapses in attention.

Vigilance – Sustaining attention over long periods of passive monitoring is notoriously difficult. Remote operators, often watching multiple feeds simultaneously, are particularly prone to reduced alertness.

Currently, Khastgir and Kim noted that research in these areas remains limited, particularly in understanding how different human factors interact and how task distribution affects overall performance in remote operation environments.

Structuring the Remote Operations Team

The tutorial also highlighted a key open question for industry: how to qualify and certify remote operators. There are currently no agreed global standards for training, licensing or assessing the competence of individuals responsible for remote assistance or intervention — despite their direct impact on safety cases.

Developing such a licensing and qualification protocol is now one of the key research directions at WMG, alongside efforts to map out the safety, regulatory, and standardisation landscape for remote operations.

Khastgir revealed that an ISO initiative is already underway, due to begin formal work at the end of this month, to establish a global standard on the classification of remote operations — covering monitoring, assistance, and driving modes, as well as associated performance requirements.

Overall, the message was clear: as autonomous driving technology matures, so too must the systems that govern the humans behind it. The next wave of AV safety will depend not just on smarter algorithms, but on well-trained, certified, and accountable remote operators.

Technology alone cannot handle every edge case, and human oversight remains indispensable. However, integrating people into automated systems raises its own design, training and regulatory challenges. Every Level 4 vehicle on the road today has a human in the loop; the question is not whether we need remote operations, but how we design them safely, efficiently and humanely.

To learn more about how these challenges are being addressed, explore the University of Wawrick’s Safe Autonomy Research Group.

Read more from InCabin and AutoSens Europe 2025:

- Automotive Advances Unveiled at InCabin and AutoSens 2025

- A Decade of Automotive Technology: Sensors, Systems, and the Road Ahead

- Public Confidence and Comprehension in Automotive Technology