Governments around the world have allocated significant funds to invest in moving powered transport away from fossil fuels. Two main avenues are being explored: battery power and hydrogen fuel cells.

Both of these technologies have different benefits and drawbacks, but in the automotive sector, battery-powered vehicles, the associated infrastructure and the underlying technology are more advanced.

However, as the rollout of electric vehicle infrastructure continues, some voices have suggested that it is merely a transition technology until hydrogen fuel cells can take over.

Drawbacks of Battery Technology

Two of the main drawbacks of battery technology for electric cars from a user perspective are range and charging time. The concern about range has even been given a name: range anxiety. Can I, the driver, complete my journey before finding and accessing suitable charging infrastructure? And then charging time: once I find a charge point, I will have to spend a good chunk of time – 30–40 minutes maybe for small vehicles – waiting for the battery to recharge. Charging points where drivers are happy to spend a bit of time, e.g. at supermarkets or motorway service stations, make good sense as a result. However, the turnover per charger is low, much lower than that of a petrol pump.

The range of an electric car is not a concern for urban driving alone, especially not for those who are able to have a home charger installed, but here there has also been a great uptake of another electric vehicle – the e-bike. This is easily charged at home and because of the very low weight of the vehicle, the battery doesn’t have to work very hard to move the vehicle itself, compared to a car. If I am going to invest in an electric car, an expensive purchase, I would specifically want it to have at least the same capabilities as a conventional ICE car – I would want to take it on road trips without worrying how far I can go and without having to spend much of my travel time waiting for the battery to recharge. This is to say that range is more of a concern when recharging times are long.

Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles

The advantage of hydrogen-powered cars is that they address both of these user concerns. The range and fuelling time for these vehicles is far superior. Refuelling a hydrogen-powered car takes around five minutes. Refuelling here could take place much as it does currently with diesel and petrol fuel, at service stations with a quick turnover. Consequently, there would not be a need to install a huge amount of street furniture on pavements throughout the country – in addition to removing street space from pedestrians, this also removes the option of protected infrastructure for electric and pedal-powered micromobility vehicles.

However, the obvious problem at the moment is that there are very few hydrogen refuelling stations in the country (UK) – not even 15. And this paucity is not the only drawback. Consider the difference between a prominent electric vehicle – a Tesla Model 3 and a Toyota Mirai, one of the few hydrogen vehicles on the UK market. The Tesla Model 3 has a WLTP-certified range of 374 miles (602km) with an average range of between 60 (97km) and 395 miles (636km), while the Mirai has a range 400 miles (644km). The Tesla battery weighs 480kg, while the Mirai’s hydrogen tank weighs a mere 5.6kg, but this light weight does not mean small in size. The Mirai has three hydrogen tanks and since hydrogen is not a very dense fuel, these take up a lot of space and consequently room that could otherwise have been used for passengers or luggage. Incidentally, the space needed for the hydrogen tanks is a real limiting factor for a hydrogen car’s range. Compared to a mode of transport where this isn’t the case – trains – the difference in range between a battery and a hydrogen train is huge. A battery train has a range of around 80km, but a hydrogen train such as the Coradia iLint has a range of 600–800km!

So given that hydrogen cars seem to create as many problems as they solve, why do some people think battery cars are a mere stepping stone to our hydrogen-powered future?

Versatile Use-Cases

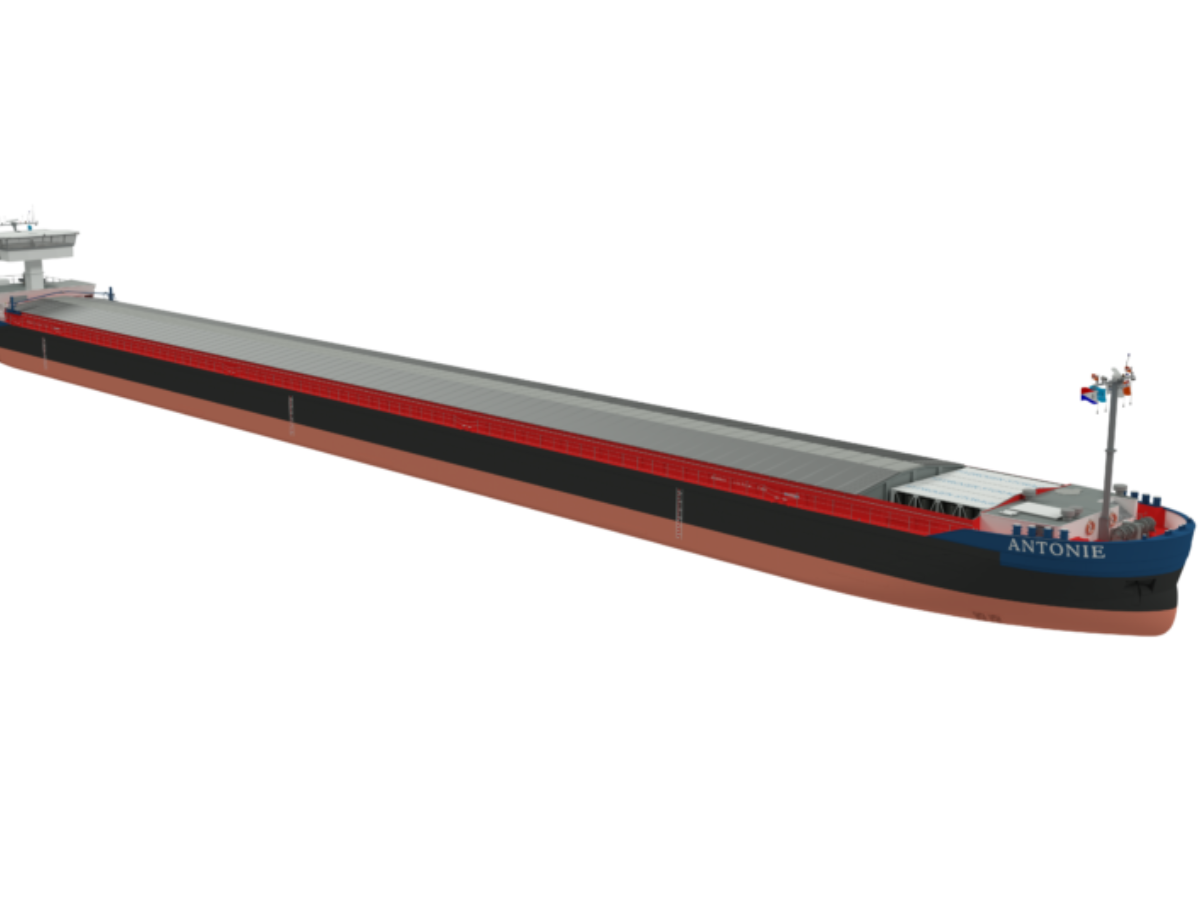

Hydrogen fuel cells can be used not just for cars but also other modes of transport such as buses – and especially long-distance coaches – ships, planes, trucks and trains. The challenge for battery-powered vehicles is long-haul operations and moving heavy goods and this is touted as one of the main use cases for hydrogen-powered vehicles. Aviation and shipping in particular come under the hard-to-electrify umbrella. In its hydrogen policy document, the EU says that “Batteries are a suitable technology for light-duty road vehicles or urban buses, but their lower energy density, compared to fossil fuels, limits their use for long-distance road transport, shipping or aviation. Clean hydrogen is a promising fuel for transport applications because it offers a higher driving range than batteries and quick refuelling. […] Clean hydrogen produced from renewable electricity and CO2 can also be used to produce synthetic gaseous or liquid transport fuels (Power-to-X). These so-called powerfuels can help decarbonise maritime shipping and aviation.”

In fact, Toyota, manufacturer of the aforementioned Mirai, is creating its Woven City, “a prototype city at the base of Mount Fuji [that] will offer a fully connected ecosystem powered solely by hydrogen fuel cells.”

The Battery Supply-Chain

One aspect of electric cars that has attracted attention of late is problems with the supply chain for certain critical minerals for the batteries. In its report, Global Supply Chain of EV Batteries, the International Energy Agency (IEA) notes that “China produces three-quarters of all lithium-ion batteries and is home to 70% of production capacity for cathodes and 85% for anodes (both are key components of batteries). Over half of lithium, cobalt and graphite processing and refining capacity is located in China. Europe is responsible for over one-quarter of global EV assembly, but it is home to very little of the supply chain apart from cobalt processing at 20%. The United States has an even smaller role in the global EV battery supply chain, with only 10% of EV production and 7% of battery production capacity.”

To meet government targets for electric mobility, the report goes on to state that “Demand for EV batteries will increase from around 340GWh today to over 3500GWh by 2030…” and that “the supply of some minerals such as lithium would need to rise by up to one-third by 2030 to satisfy the pledges and announcements for EV batteries […]. For example, demand for lithium – the commodity with the largest projected demand-supply gap – is projected to increase sixfold to 500 kilotonnes by 2030 in the APS [the Announced Pledges Scenario], requiring the equivalent of 50 new average-sized mines.”

Where Does This Leave the Private Car?

There are obviously problems with all power sources. Investment in these technologies will reduce these issues over time. And as with modes of transport where there is not one mode that is best for all journeys, the same can be said for fuel. Different power sources for different use cases. Vehicle manufacturers will invest in both technologies and consumers will consider the pros and cons for themselves, meaning we are likely to see a mix of power sources. Hydrogen-powered cars will likely increase in market share as the infrastructure becomes more established, but it does not seem likely they will replace electric cars.