Nominally this is about the Ideas Train panel discussion ‘What Can Town and Country Learn from Each Other?’ held at InnoTrans today.

And it is about what the panelists said. But ultimately the topic was behaviour change. How can we move away from cars – both in rural and urban areas.

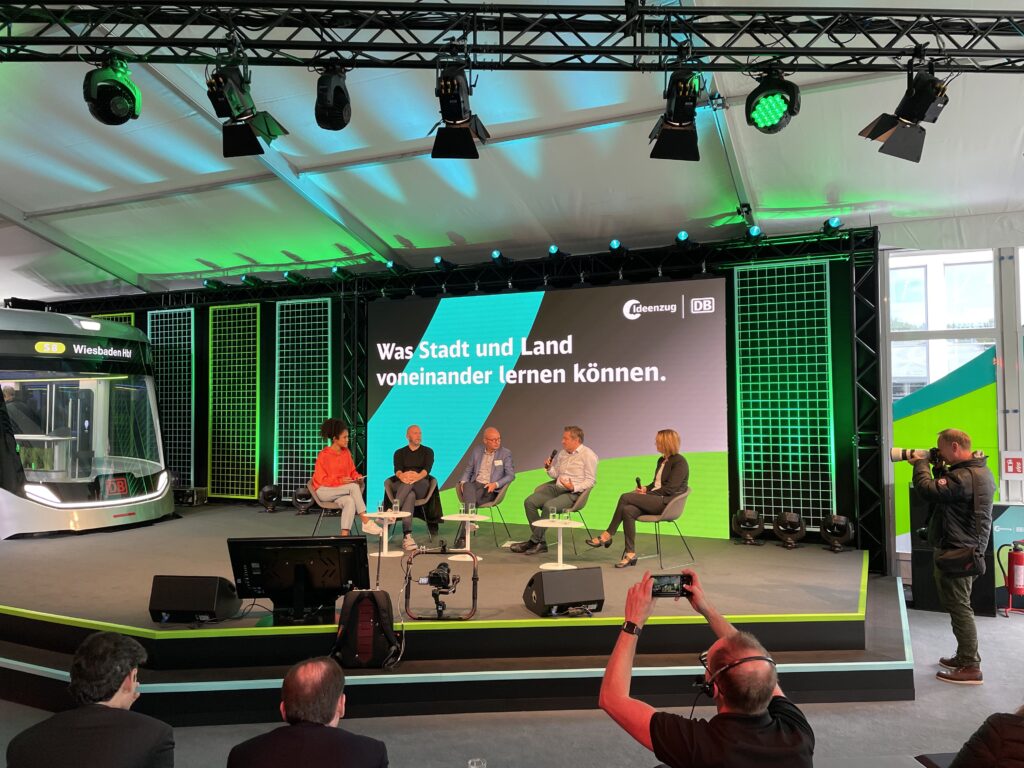

The panel’s participants were Stefan Carsten from the Zukunftsinstitut, Frank Klingenhöfer from DB Regio, Jan Schilling from VDV and Claudia Nobis from the German Aerospace Center in DB’s Ideas Train venue at InnoTrans 2022.

(l-r: moderator; Stefan Carsten, Zukunftsinstitut, Frank Klingenhöfer, DB Regio; Jan Schilling, VDV; Claudia Nobis, DLR)

Claudia Nobis stressed early on that people, regardless of where they’re living, all want the same thing. They make the same kinds of trips to the same kinds of destinations and they make roughly the same number of trips, too.

The division between rural and urban areas, with regard to transport, lies fundamentally in the services that are accessible to their residents. Consequently, car ownership in rural areas is around 90%. The reason for this was clear, Ms Nobis said: public transport takes far too long and if it takes substantially longer than driving, it’s no alternative at all.

Conversely, Mr Carsten said the only reason his family – resident in Berlin – still owned a car was because they were otherwise unable to access rural areas in any other way, meaning lack of rural connectivity also keeps car ownership in urban areas higher.

Public transport service frequency in rural areas is also a problem. Oftentimes the services that exist work well but there are too few of them to be routinely useful to people. Rural areas have few residents so higher-capacity vehicles on fixed routes are not profitable and therefore not offered.

When looking at the data, driving takes less time for rural residents than public transport. However, driving is also faster for their urban counterparts, oftentimes, than taking public transport. In this regard, despite the quite different service provisions, the two opposing regions are similar.

The question then turned to how people could be encouraged to turn away from private vehicles given the reality of the accessibility, convenience and flexibility private vehicles offered, with 500,000 new vehicles on German roads every year.

Even in the Netherlands, where cycling, walking and public transit culture has been developed for 50+ years, when young people reach the age when they are legally allowed to drive, there is a marked drop in cycling and public transport use.

The truth is, cars are extremely convenient for those who have access to them.

You might wonder: what’s the problem? Why not just drive? Well, there are a number of reasons. A central one of course – the topic du jour – is climate change. Not only do private vehicles contribute hugely to greenhouse gas emissions, the sheer amount of land given over to roads and parking is not good from an environmental perspective.

Beyond that though it’s an accessibility question: cars are expensive and not everyone can drive them. The young aren’t legally allowed. They too should have the ability to get around. Older people often lose the ability to drive with age – either due to medical conditions or because their insurance has sky-rocketed. If they live in an urban area where public transport exists, then they are lucky. If they live rurally where there are no services, they become trapped.

So what is the fix? It is threefold: some push, some pull and some better planning.

To start with the latter, the panelists were agreed that rural areas have been made amenity-poor. We talk about the 15-minute city for urban areas, but we need walkable amenities in rural areas too in order to diminish the need for travelling distances that necessitate driving in order to access them. The corner shop. The local school. The village pub. This has the additional benefit of placemaking. And it’s a ‘no thank you!’ to the concept of dormitory towns.

In fact, building for cars – wider and wider roads with large car parks – so that rural or out-of-town residents can access city amenities and jobs also means that amenities within urban areas become increasingly spread out, reducing their walkability and rideability – and increasing air and noise pollution – for their residents. Rural and urban areas are not isolated systems.

So what about the pull factor? Germany’s €9 ticket (the monthly charge) for non-high-speed rail services as rolled out by Deutsche Bahn this year for three months was highly praised by the panelists. The data gathered has shown that the offer was easy for people to understand, they were happy to return to public transport to use it after covid and 15% of people who purchased such a ticket were people who had not previously been public transport users. The key message: we must make using public transport easy. The people who bought these tickets made experiences of being able to use public transport and this can create behaviour change.

Words of caution were also put forward. People don’t just travel from A to B. They travel from home to work, stop at the shops afterwards and maybe pick children up from extra-curricular activities before returning home. If any link in a public transport chain allowing them to make such trips without a private vehicle were to fail, the whole chain fails. An example: a bus service can’t stop running at 6pm just because that’s when the commute is over. We have to consider all users.

Lastly, the push factor. If we are to meet climate change goals and by extension keep the planet habitable for humankind, Jan Shilling was clear. “We don’t have 50 years,” he said. “We also need to tackle this with legislation.”

Claudia Nobis agreed. We need to create pressure points. Factors such as high parking charges and traffic jams will cause people to question their mobility behaviour. If drivers look out of their car window and see buses moving freely on dedicated bus lanes, they might be encouraged to make the switch – bus lanes in particular because unlike railway lines they are quick and cheaper to create. We need the political will to build the infrastructure to give people alternatives and then we have to make driving less convenient.

Because if we could have a do-over, how would we design our built environment? Ms Nobis said if we could go back we wouldn’t pick the private vehicle. We’d design a better way for people to get from A to B. We would design our cities differently to not have car dependency built-in, Jan Schilling followed up. Frank Klingenhöfer said we’d look at people’s needs first and provide solutions second, rather than vice versa.

Examples from Paris to Amsterdam to Xiong’an in China show: where there is the political will and leadership, we can design cities of 1m+ residents to be car-free and we can create a culture change that residents buy into. That’s good for the planet and good for liveability too.